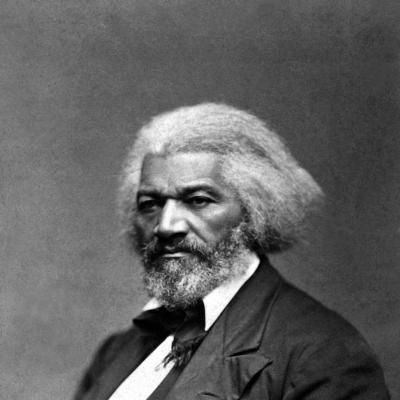

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery in Maryland in February of 1818 and died on February 20, 1895, having lived the final 57 years of his life as a free man. Douglass liberated himself from slavery in 1838 with the help of Anna Murray (soon to be his wife), who was a free black woman, Abolitionist, and member of the Underground Railroad living in Baltimore. She got him the money, disguise, and identification papers that he needed to carry out the plan of boarding a northbound train dressed as a sailor and thus make his way to New York City.

After escaping slavery, Douglass joined with the white Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, but eventually split with Garrison over the proper interpretation of the Constitution. Garrison thought it was a pro-slavery document that needed to be discarded, whereas Douglass came to believe that it was a “glorious liberty document” that nowhere contained “the right to hold property in man” and that properly interpreted “would put an end to slavery in America.”

Douglass wrote and lectured tirelessly in order to defeat slavery and then, after the Civil War, in order to better the lot of black Americans, to secure women the right to vote, to promote immigration and a multi-racial conception of American identity, and to advance equality and civil rights for all.

In addition to his many speeches and articles, Douglass wrote three autobiographies:

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845)

My Bondage and My Freedom (1855)

Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881/1892)

The Library of Congress’s Frederick Douglass papers, 1841-1967 are available here.